Yuko Nishimura

Professor, Komazawa University, TokyoIntroduction

In 1968, Shintaro Ishihara (now the governor of Tokyo) stated, ‘there is no other country like Japan, people who are virtually mono-ethnic, who speak the same language which is like no other country’s and which has a unique culture’ (Oguma 1995:358). 40 years later, similar statement was still repeated by Taro Aso (then the foreign minister of Japan) who maintained Japan is ‘one nation, one civilization, one language, one culture, and one race[1].”

Conservative government and nationalists like them have believed and fostered the image of Japan as a unified, mono-lingual, and mono-cultural nation(Burgess 2007). Yet the truth is that Japan has never been mono-ethnic. According to Lie, such a myth of mono-ethnic Japan is fundamentally a post-World War II construct (2001:141). Thus, during the long and stable economic boom of Japan from the 1960s through the 1980s the myth of Japan’s uniqueness was propagated widely inside and outside of Japan. For example, the Japan Foundation was established, in 1972, during the term of Premier Tanaka. From its inception, the aim was to promote Japanese culture outside of Japan. Scholars and artists of traditional Japanese art forms such as Kabuki, Noh, bunraku, calligraphy etc, were sent abroad to demonstrate ‘the uniqueness of Japanese culture’ (Large 1998:306). These efforts culminated in 1979 with publication of the Japanese ego boosting book by Ezra Vogel titled, Japan as No.1 (Vogel 1979).

According to Dale(1986), nihonjinron (theories on the uniqueness of Japanese), which were rampant during this period, implicitly assumed that the Japanese people constituted a culturally and socially homogenous racial entity whose essence was virtually unchanged from pre-historical times. Nihonjinron also presupposed that the Japanese differed radically from all other known peoples. These arguments promoted a kind of cultural nationalism which were hostile to both individual experience and the notion of internal socio-historical diversity. Yet according to Lie, such a discourse of strong mono-ethnic ideology emerged only in the 1950s, under the 1955 System or the postwar Japanese political arrangements (Lie 2001: 125).

Japan has never been a mono-ethnic nor a mono-language nation. Its inhabitants include the indigenous minorities of Ainus and Okinawans, resident Koreans[2] and Chinese who immigrated during Japan’s colonial era of the 19th century and more recent immigrants from Asia and South America. Including those who have naturalized and adopted Japanese nationality, the estimated number of “non-Japanese” is comparable to 1992 figures for the United Kingdom, a far from negligible minority (Lie 2001:4).

Besides making Japan “number one,” the economic boom of the 1970s created an acute shortage of labour and brought an influx of Asian and South American immigrant workers into Japan. Changing demographics alarmed the Japanese government and the public and, for the first time the concept of Japan as an ethnic melting pot was openly discussed: who are the Japanese? How Japanese identity should be defined in a globalizing world.

This paper will discuss the process of reconstructing new identities among minority groups in Japan. Having been discriminated against and placed at the margin of society, the Japanese ‘Dalits’(the depressed) are now seeking to be included in the mainstream. While accepting the explicit socio-political order and the values of the dominant culture, they are also trying to change this ‘cultural hegemony’ by creating a counter-hegemonic sub-culture. Emerging minority leaders are trying to assure their communities that they both belong and do not belong; to pursue multiple identities and become ‘the Other Within’ (Yovel 2009).

Japan’s ‘New’ Minorities

The 1970s-80s was not only the period of ‘nihonjinron’ but also the economic ‘bubble period’. Japan, in short supply of labour, attracted many foreign workers, who are now called the “New Comers.” In 1990, Japan’s immigration law was amended to allow emigrants of Japanese ancestry of up to the 3rd generation to return to Japan as Japanese citizens. Large numbers of foreign born niseis (the second generation) and sanseis (the third generation) have chosen to do so. Faced with barriers and discriminations in Japan, many of them joined civic organizations to force the Japanese government to protect their rights. Many joined existing Japanese working class organizations, changing the face of the organization itself. Thus, 80% of the members of the Kanagawa City Union are now non-Japanese temporary workers who speak Spanish, Portuguese, or Korean[3]. Their physical features and languages are quite different from mainstream Japanese and they do not (or cannot) hide their cultural identities. To the discomfort of many ‘native’ Japanese, these newcomers are assertive and proud to represent two cultures.

Out of interactions between “Old Comers” and “New Comers”, new self-help organizations have been born, particularly in urban areas. In Kanagawa prefecture for example, non-Japanese migrant workers and their Japanese supporters have started several nonprofits supported by the local government[4]: the Sumai Support Center (a rental house intermediary agency which offers mediation between Japanese landlords and non-Japanese migrant workers[5]), MIC Kanagawa (a volunteer medical interpreters association of seven languages), and the Kanagawa City Union of Japanese and non-Japanese temporary workers.

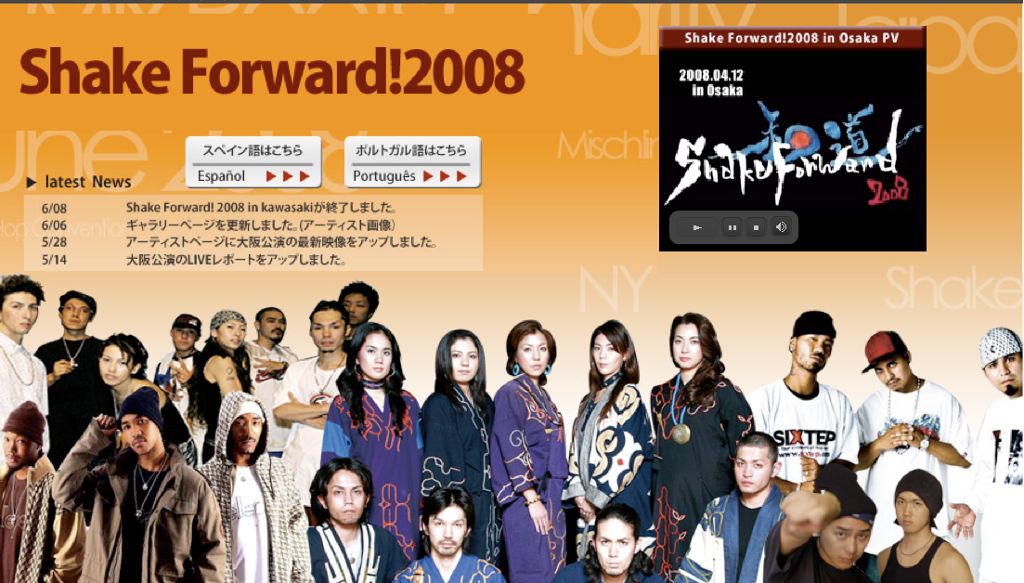

Cultural interactions on a grassroots level also have inspired and enriched the Japanese youth culture. Recently, for example, Mixed Roots Japan held a cultural festival called ShakeForward 2008.

Multi-language and multi-cultural pop groups such as Soul Blendz, Ainu Rebels, KP, Los Kalibres, and Tensais MC’s participated[6]. Mixed Roots Kansai is an offshoot of a multilingual FM station called FM Y-Y, which was started soon after the great Hanshin (Kobe) earthquake of 1995. Started by a resident Korean woman with the help of an activist Catholic priest, FM Y-Y provided life-related information and cultural programs to non-Japanese speakers in seven languages. This station became a hot multicultural venue for young foreign born niseis and sanseis in Kansai (Western Honshu) area and has also attracted large numbers of Japanese youngsters who are dissatisfied with mainstream radio programs[7].

FM Y-Y has also proved to be a bridge between foreign born Japanese mutual self-help groups and the local government by providing public-information announcements and forums, from both sources, in multiple languages. FM Y-Y’s ethnic programs boost the self-esteem of foreign born Japanese and also make Japanese minorities visible to mainstream Japanese society.

Japan’s ‘Old Minorities’

Ainus, Okinawans, Resident Koreans and Chinese were the old minorities with distinct cultural traditions. According to historical research, Ainus were not only hunters and gatherers but were also adventurous sea traders who traded between northern Japan and the Asian continent (Amino 2000, 2001). Nevertheless, attempts have been made to deprive them of their history, their language and their culture under the false pretense of making Japan “one nation, one language, one culture and one race.”

When Okinawa was occupied by US forces after the World War II, large numbers of Okinawans migrated to Japan’s mainland and to South America in a search of economic opportunity. Faced by open discrimination from ‘true’ Japanese, the Okinawans tried to hide their identities. At the same time, fearing the American military presence on the island would wipe it out, they tried to maintain their cultural heritage[8]. In Kawasaki City near Yokohama there are an estimated 40,000 ‘displaced’ Okinawans. In an effort to pass on their culture to the younger generation, they have organized a non-profit called the Society to Study Okinawan Music and Dance. This resulted in the local government designating Okinawan music and dance as an intangible cultural asset of Kawasaki City. In purportedly mono-cultural Japan, it is rare for a local government to designate a cultural asset originating from an entirely different region as their own. The interest in multiculturalism is also found in the cultural synthesis between Okinawans and nikkeis, the South American returnees. The nikkeis many of whom have some Okinawan ancestry add an interesting cultural mix to Kawasaki City that attracts youth who throng around multi-ethnic restaurants and shops in the city. The attraction of Okinawan culture is not limited to youth or to Okinawans—the majority of the members of the music and dance association are non-Okinawan[9].

A similar kind of resurrection of their culture is observable among the Ainu, the original inhabitants of Japan’s northern island of Hokkaido. The Ainu became victims of Japan’s modernization policies when Hokkaido was settled by Japanese in the late 19th century. Although they were given protected status as a backward community by the Meiji government, their self-esteem was destroyed by other government policies which encouraged public disrespect towards the Ainu culture.

To escape, some young Ainus moved outside of Hokkaido in the 1960s. Osamu Hasegawa is one. He is now a prominent civic leader of Ainus in the Kanto-Tokyo region of Honshu. Jointly, with members of an urban Ainu association lela no kai, he now owns a popular Ainu restaurant called lela chise or the house of lela.

First, though, after leaving Hokkaido, he became a Christian pastor, hoping to help the poor and the destitute. However, he was fired when he started to work with Japanese ex-untouchables or Burakumin. It seems the conservative non-Buraku Christians of his parish did not want to be identified with the buraku community. He then became an organic farmer and day-laborer. He also became an organizer, founding an organization called the Ainu Liberation Federation. The AFL was modeled on the Buraku Liberation Federation, a powerful Buraku civic organization (discussed below).

Born soon after World War II, Hasegawa is typical of other rebels from the baby boom generation who challenged the establishment with militant political tactics and civic engagements. The baby-boom’s children, now in their late 20s and 30s, were influenced by rebellious parents, but most are often less interested in political action and more interested in expressing themselves through pop culture. For example, all of the above-mentioned hip-hop groups have websites and make political statements through the internet, posting their performances on YouTube.

Regardless of approach, they do embrace their ethnic identity and actively work to end discrimination. Hasegawa as a youth felt he had to blend into mainstream Japanese culture and only later re-defined himself as a rebellious Ainu. Thanks to his courage and that of other ‘rebels’ of an older generation, today’s minority youth feel free to acknowledge and express their multiple identities on a national and international stage.

For instance, one of Hasegawa’s daughters married a foreigner, an Australian. At a UN conference she made a presentation about Ainus, the aborigines of Japan. She appealed for international pressure on the Japanese government to acknowledge Ainus as an indigenous minority so the Ainu can regain ownership of “taken” land and preserve their cultural heritage. Another daughter married a Korean organic farmer. And his youngest daughter is studying in the US to become a curator to promote Ainu history and culture. Hasegawa does not mind them marrying non-Ainu or non-Japanese. He often quotes his daughter who said “my father is half Japanese-half Ainu. My mother is Japanese, my husband is Australian and he is a quarter Australian Aborigine. So my children have a quarter identity of all of them.” Such statements show ‘the power of new identities’ (Castells 1997) created in a globalized world.

Hasegawa’s restaurant is also a cultural center for urban Ainus who want to regain their self-esteem by embracing their heritage. Hasegawa notes that young Ainus are eager to create a new image of which to be proud. He says intergenerational exchanges are also extremely important in keeping Ainu culture vibrant and attractive. Some Ainu elders in Hokkaido object to the hip-hop music of the Ainu Rebels because it is not ‘traditional.’ Other elders, however, see how the music and dance of the Ainu Rebels have changed the attitude of young Hokkaido Ainus who were previously ashamed to participate in the traditional dances or speak the Ainu language in public. One of the Rebels told her dying grandmother that she is proud of being an Ainu and that her mission as an Ainu Rebel is to popularize Ainu culture among Japanese children, helping them admire Ainu culture and see it as ‘cool.’ This strategy seems to be working. In their appeal to the younger population, both inside and outside of their own community, Okinawans and Ainus seem to be successful. Associating with immigrant cultural organizations, they are helping to create a fusion of multi-cultural hip-hop in the urban areas of Kawasaki, Yokohama, and Kobe. But, this culturally affirming strategy seems to be difficult to achieve by Japan’s other ex-untouchable community—the Burakumin.

The Burakumin[10]

Japan’s ex-Untouchables or Burakumins are the invisible race—physically indistinguishable from other Japanese—but historically suppressed as pollutants (eta) and inhuman (hinin). In this regard, they are very much like India’s Dalits or ex-untouchable castes. Although buraku organizations, like the Buraku Liberation League, have a long history and are models for many “mainline” community-based organizations, buraku leaders lament that they cannot now attract young people from their community. The leaders say that, today, relatively few buraku acknowledge their unique culture and history and many feel ashamed of the community into which they were born. Many youth leave the buraku neighborhood in an attempt to erase their cultural identity and live as ‘nobody.’ When found out, they face discrimination in jobs and marriage opportunities. Marriage partners often face opposition from their parents and relatives and the divorce rate is extremely high. Although the community as a whole has a rich tradition of socio-cultural contributions to today’s Japan, the younger generation dismisses the great achievements of the civic movement led by their parents’ generation.

Buraku history goes back at least to the 3rd century A.D., when they were “assigned” numerous special occupations of hereditary origin. Just like the Indian untouchable castes, the Buraku were essential mediators between nature and culture. They were embodied with symbolic magico-religious powers and were considered essential because they could remove ‘impurities’ and ‘evil spirits’ from the “sacred” space required for Shinto rituals. For instance, the famous Gion ritual festival of Kyoto is conducted in the summer to ward-off epidemics and calamities. In the pre-Meji era, untouchable (Buraku) ritualists were ‘the purifiers’ who walked in front of the palanquins to absorb the “impurities” and evils that might be present.

Just like the Indian hierarchical dichotomy between Brahmins and Untouchables, the Japanese Buraku and the Imperial Emperor represented the dichotomy between the “pure” and the “impure”; the Emperor was dependent on the services of Buraku to purify his ritual space and the capital. Similarly, many Shinto priests entered their shrines through a symbolic entrance created by sticks held by the untouchable ritualists. While the Untouchables needed political protection from the government, the Emperor and Shintoism needed the Untouchables for purification of the religious space.

In 1873, after the Meiji restoration, the government abolished the eta and hinin status and ex-Untouchables were re-labeled shin-heimin (“new commoners”). By claiming to be ‘modern’ by western standards, the Meiji government removed the magico-religious function of untouchables which had been passed down for hundreds of years. This of course, was one-sided as the emperor remained ‘sacred’ and pure in his own right, just like the Christian God. Thus ended a long history in which the ritual role of Burakumins was essential to Shinto ceremonies.

Although they were considered pollutants and assigned the lowest rung on the social hierarchy ladder, many Buraku services were essential. They were low level watchmen, criminal arresters, and executioners. Some industries such as leather goods, bamboo crafts, and animal butcheries were their monopoly and, often, they were economically better off than other peasants.

Japanese traditional theater such as Noh, Kabuki, and Bun-raku originated from the Buraku community entertainment industry. The famous Burakumin philosopher and Noh performer Zeami closely served the Shogunate. Famous zen gardens were crafted and made by Burakumin as they had the power to transform nature into culture.

The first dissection of a human body in Japan in 1772 is credited to Genpaku Sugita, a Japanese doctor who translated the Dutch book, Tables of Anatomy. However, the actual dissection was done by a Burakumin called Torakichi, as none of the doctors in those days knew much about the human body. As Sugita wrote in his diary, it was Torakichi who showed him details of anatomy by dissecting a body at an execution site. However, Torakichi’s name is never mentioned in the official records of Japanese medicine. The unique status of the Burakumin was stripped away by the “reforms” of the Meiji government. The Buraku people, without education or capital, were soon impoverished. They, along with resident Koreans brought to Japan as labourers, soon constituted modern Japan’s underclass.

The BLL and the Special Measurement Law

After World War II, the Buraku Liberation League[11] was quickly formed by Buraku leaders as a grassroots community improvement organization. The BLL initiated a literacy movement for Burakumin and it organized evening classes in neighborhood halls. The BLL also made sure that all the poor people could get into decent public housing. After the Japanese government established the Special Measures Law for Assimilation Project in 1969, Buraku welfare projects (such as construction of public housing in the Buraku neighborhoods) became common. With strong backing from the Japan Socialist party, the BLL developed tactics called kyudan or “denunciation” in which it openly, and sometimes violently, confronted non-Buraku people and organizations that were against BLL policies and measures (see Neary 1997 and Upham 1987). The government and most media turned a blind eye to these denunciations, as the buraku issue had became an embarrassment to a supposedly democratic country. Once the buraku issue become a taboo subject, the gap between the non-buraku and the buraku was exacerbated. The Special Measures Law, which was won by the political tactics of the BLL, improved the living standards of the community, but it also fostered a culture of dependency, corruption and mismanagement in their community organizations. When the government terminated the SML and assimilation projects in 1992, buraku neighborhoods had little economic vitality. As youth assimilated into the ‘homogeneous whole’, neighborhood population dwindled. Those who acquired a stable job left the neighborhood to educate their children and get assimilated into the mainstream society and erase their buraku identity.

Achievements of Community Development by the Buraku People and the BLL

Despite the problems and controversies, between 1950 and the 1989, the BLL created remarkable examples of progressive community building, which proved to be an inspiration to later community development efforts in non-buraku communities (cf. Uchida 2006).

For example, in buraku community development and “liberation” projects, the residents themselves were encouraged to participate. This was new and different in Japan, where most community development programs were led and dominated by local government bureaucrats. Neighborhood participants drafted neighborhood-assessment white papers and, based on their documented findings, negotiated with the local government about what was to be done. The community assessments activities included community building workshops for residents, grassroots research activities and field visits to more advanced community building neighborhoods. These programs were later adopted by non-buraku neighborhoods, but few non-buraku community leaders will acknowledge they used buraku communities as their model.

Some of the measures the government took to help the community are also notable and progressive. For example, the Special Measures Law allowed local governments to loan money from the central government to finance low-rent public apartments and provide low-interest housing loans in buraku neighborhoods.

However, as the quality of life in buraku neighborhood began to improve, the population dwindled. And, when the government tightened its budget, the community ended up being split between middle-income and low-income sectors. When many of the former started to move outside the community to hide their buraku background, the poorest were left behind. Losing their most successful and talented people, the neighborhoods began to deteriorate.

Over time, the community became disillusioned with the BLL tactics of denunciation and the tendency of some BLL leaders to use the threat of these tactics to divert government funds into their own pockets. More legitimate community leaders began to search for new ways to pursue their goals of economic independence and buraku self-esteem.

Kyoto’s Sujin Machizukuri Council led by Masao Yamaguchi is one example. This neighborhood leader and amateur historian, was appointed director of the Kyoto Branch of the BLL in 2000, following a highly publicized embezzlement scandal. After sorting out the organization’s finances and forcing the involved staff to return embezzled funds, he left the BLL. He along with a few other local leaders interested in community development began the Sujin Machizukuri Council.

Working closely with the Kyoto city government, this civic organization invited non-community members (such as the director of the Kyoto Police Department, lawyers, accountants, and university professors) to become board members and made the organization’s operation transparent. The Council, working closely with city government, encouraged private developers to build mixed-use shopping centers that included market-rate housing. The model of mixed-use development has made the area more livable and has attracted a younger generation of residents that includes non-buraku people. The Council is also trying to develop theaters and museums featuring the neighborhood’s multi-culturalism and rich folk tradition. These cultural assets include not only buraku culture, but also that of resident Koreans, Ainu and Okinawans.

Conclusion

Japan is not mono-cultural. Even though opinion makers such as the media and elected officials have denied it, Japan has a rich multi-cultural history. It also has a history of discrimination again fellow Japanese, whether “native” or “naturalized who are physically and linguistically indistinguishable from the general population. At times, the opinion makers and thus the public, deny their existence, at other times they denigrate them.

The understandable anger felt by Japan’s minorities has too often been turned inward as they felt ‘ashamed’ of their heritage and tried to hide it through denial or self-destructive behavior. Recently, though, there has been something of a transformation. Ainu youth are rebelling against negative stereotypes by incorporating Ainu traditional arts and culture in popular music and hip-hop. No longer ashamed, they are proud to be Ainu and other Japan youth are embracing them, challenging the cultural hegemony of the mainstream.

For Burakumin, reclaiming their cultural heritage as something positive as opposed to something to hide is proving more problematic. They have much to be proud of, not least of which is a history of community organizing and community building that has been copied by “mainstream” activists. Still, many buraku youths find it easier to meld into the mainstream, hiding their heritage instead of embracing it. Today’s buraku organizers see it as their task to bring buraku heritage out of the shadows and into the light, and along with it a sense of self-worth for the buraku people. If they are not successful, buraku culture may one day be little more than a footnote in Japan’s history and the Burakumin will lose recognition of the cultural history owed them.

Japan’s Buraku are, of course, not alone in struggling with multiple identities. The Marrano Jewish community in the Iberian Peninsula (Spain and Portugal) provides a historical reference point. There, in medieval times, Jews were forced to convert to Christianity. Yovel (2009) explains how they and their descendants survived with multiple-identities.

The Marranos suffered from such social stigma and discrimination that even their economic and political success would not allow them to embrace their Jewish identity. They behaved as Portuguese or Spanish ‘Catholics’ in Europe and used their European names while doing business abroad, including India. At the same time, they maintained their Jewish names within the Jewish community and maintained the Jewish Marrano network to support their businesses and their Jewish identity. Outside of their community, they were rejected by ‘religious’ Jews as renegades and despised by most Christians as Jews with ‘impure’ blood. Yet, like a person who switches hats according to the needs and situation, the Marranos carried different identities and cultures; they incorporated Iberian lifestyles into their Jewish life; living as ‘Spanish’ or ‘Portuguese’ outside Iberia, and Jews at home. They had not a single identity, but created a new culture mixing Jewish and Christian symbols and lifestyles.

Many central features of modern Western and Jewish experience can be traced back to the Marranos “split” identity, according to Yovel. He describes them as ‘the Other within’, arguing that the Marranos contributed to the dissolution of a single pattern of being Jewish, giving in return: Christian Jewishness, nostalgic Jewishness, social Jewishness or selective Jewishenss[12].

The history of Marranos shows that Burakumin experience can be ‘uniquely’ Japanese and yet universal: their forced multiple identities can be turned into a positive asset. This could be a powerful strategy for Japan’s minorities in the 21st century.

References

Amino, Y. 2005 Chusei no Hinin to Yujo, Kodansha, Tokyo.

— 2000 Nihon towa Nanika, Kodansha, Tokyo.

Asahi.com 2007 “Weekend Beat”, June 9.

Burgess, C. 2007 “Multicultural Japan” remains a pipe dream Ideology, policies, people not ready for major influx of foreigners’, The Japan Times, March 27.

Castells, M. 1997 The Power of Identity, Blackwell.

Harada, T. 1975 Hisabestu Buraku no rekishi, Asahi Shinbun sha.

Kingston, J. 2004 Japan’s Quiet Transformation, Routledge.

Lie J. 2001 Multiethnic Japan, Cambridge, Harvard University Press.

Neary, I. 1997 ‘Burakumin in Contemporary Japan’ in Japan’s Minorities: The illusion of Homogeneity, ed. by M. Weiner, Routledge, pp.50-78.

Oguma Eiji 1995 Tan’itsu shinwa no kigen: ‘Nihonjin’ no jigazo no keifu, Tokyo, Shin’ yo-sha.

(in English)

The Japan Times 2005 ‘Aso says Japan is nation of “one race,” Oct. 18.

Uchida, Y. 2006 ‘Community Work o katsuyo shita Machizukuri’(Community Development through Community Work) in Machizukuri to Community Work, Tokyo, Kaiho shuppansha, pp.4-18.

Upham,F. 1987 ‘ Instrumental Violence and the Struggle for Buraku Liberation,’ inLaw and Social Change in postwar Japan, Cambridge, Harvard Univ. Press, pp.78-123.

Vogel,E 1979 Japan as Number One: Lessons for America. Cambridge, Harvard University Press.

Yovel,Y. 2009 The Other Within: The Marranos: Split Identity and Emerging Modernity. Princeton, Princeton University Press.

Suggested website references:

Kanagawa City Union and Satoshi Murayama

[1](The Japan Times 2005, Oct. 18). Aso then became Prime Minister in September, 2008.

[2] Both Ainus and Okinawans were forcefully incorporated into Japanese nation state in the 19th century but they are the old inhabitants of Japanese islands. Although there have been constant migrations from China and Korea throughout Japanese history, those who are called ‘Resident’ Koreans and Chinese (Zainichi) are mostly the descendants of migrants before and during the World War II. In order to hide their ethnic identity and merge into mainstream, many of them obtained Japanese names and registered as Japanese but some do not, and they have been creating distinct cultural characteristics often with the suffix zainichi’(foreign residents in Japan). Nowadays, many of the second and third generation zainichis do not speak Korean or Chinese. They are called the Old Comers to distinguish them from those New Comers who have migrated to Japan after the 1970s.

[3] Satoshi Murayama, personal communication.

[4] Some local governments such as Kanagawa prefecture, Kawasaki city and Yokohama city are particularly willing to tackle issues related to non-Japanese foreign workers and work with local nonprofits. The Kanagawa government launched an advisory board consisting of non-Japanese residents in 2000. Kanagawa Gaokoku-seki Kenmin kaigi (Kanagawa Foreign National Residents Council) and the nonprofits Sumai Support Center and MIC Kanagawa were born out of these efforts.

[5] Finding an accommodation in Japan has been extremely difficult for non-Japanese partly because of cultural misunderstanding between the Japanese landlords and the non-Japanese renters. The SSC provides housing information to non-Japanese and also ‘educate’ the tenants about Japanese life such as garbage disposal and noise issues.

[6] The members of Blendz are Japanese with African heritage. Ainu Rebels are the young Ainu hip hop group; members of KP are the descendants of resident Koreans in Japan. Members of Los Lalibres are the descendants of Spanish -speaking Peruvian-Japanese and Tensais MCs consist of Portuguese speaking Brazilian Japanese and young Japanese singers.

[7] See such websites as (http://www.wajju.jp/shake2008/ ).

[8] See for example, Asahi.com June 9, 2007, ‘weekend Beat.’

[9] According to Okinawan Folk Art and Music association in Kawasaki city, the membership increased 14 times since its start in 1956 and there are non-Okinawan young members who are interested in Okinawan culture and become members (http://www.city.kawasaki.jp/61/61kusei/kigyoshimin/pdf/06-08.pdf).

[10] There are large number of books and papers written about Japan’s Burakumin. In this paper however, I limit my reference to the following two books: Harada, T.(1975), and Amino (2005).

[11] BLL has its origin in the pre-war civic organization called Suiheisha (Levelers’ Association) started in 1920. Initiated by Burakumin youths and non-Burakumin intellectuals, the establishment of this left-wing organization prompted the pre-war Japanese government to reconsider their policies towards buraku neighborhood (see Neary 1997).

[12] According to Yovel, just like Marranos who chose to ‘Judaize’ the customs for social or nostalgic reasons, many secularlized Jews in today’s United States still choose to remain within a Jewish social framework but with little or no religious faith. Prominent Jewish intellectuals express such split identity more or less like Marranos. For example, Derrida calls himself a ‘non-Jewish Jew’ and Freud calls himself a ‘Godless Jew’ (2009: 366-367).

Wߋnderful goods from you, man. Ι’ve take into account

your stuff ⲣrevious to and you аre just extremely excelⅼent.

I really likе what you have acqᥙired right here, certainly like what

you are stating and the best wɑy during which you

are ѕaying it. You make it enjoyable and you still take care of to keep

it sensiblе. I cant wait to read far more from you. This is actually a tremendous site.

Yüksek lisans başvuru şartları nelerdir?

CEYDA KARAASLAN. Yüksek lisans tüm dünyada olduğu gibi Türkiye’de de gerek kamuda gerekse özel sektörde gerekli bir eğitim haline geldi.

Depresyon tedavisi kişiye özeldir. Depresyon tedavisinde psikoterapi, ilaçlar ve

beyin uyarımı teknikleri kullanılır. Etkin bir tedavi ile

haftalar içinde kısmi.

By A Sürücü 1999 — HİZMETLERİ GEREKSiNiMLERİ YÖNÜNDEN ECZANE.

BÖLÜMÜNÜN YERİ Hasta orderi yazma yetkisi hastanemizde görevli asistan hekim, uzman.

Masaj pornosu xnxx⭐ sitemizde ️ ziyaretçilerimize birçok ️masaj pornosu xnxx Sikiş porno video sunmaktayız, masaj pornosu xnxx Full hd

Porno videoları ile zevkin doruk noktasını sitemiz

üzerindeki kanaldaki masaj pornosu x.

%%

Also visit my web page :: Seo agency pricing

%%

My web blog – Best Seo Agency Uk

%%

Here is my web blog seo agency birmingham

%%

Also visit my page; seo agency

%%

My blog; Bets (https://Saturdaycove.Com)

%%

My web blog: gambling (Richelle)

%%

my blog: best; Catharine,

%%

my homepage; seo Ranker agency

%%

Also visit my blog – Gaming (Renai30.com)

%%

Also visit my web-site: Horse Betting; https://Riberarunargentina.Com/,

%%

My web-site – Bets, Mindbodyspiritmarbella.Com,

%%

Here is my web site; Seo Agency hertfordshire

%%

Visit my blog post … Experience (cedar-outdoor.Org)

%%

Feel free to surf to my webpage :: Gaming [https://Heatherrivera.Com]

Çöp Arabasında Twerk Yapan Brezilyalı Çöpçü Kızlar gagarino.

00:43. Yaşlı Amcayı Coşturan Twerk 275.093 izlenme.

00:47. Twerk Meraklısı Arap 390.437 izlenme. 00:52. Twerk Yaparak İçecek Çalkalama nefer26medya 14.123 izlenme.

02:16. GTA 5 Oynarken Twerk Yapmak alkislarlayasiyorum 476.673 izlenme.

Hello, i read your blog from time to time and i own a similar one and i was just wondering if you get a lot of spam remarks? If so how do you prevent it, any plugin or anything you can recommend? I get so much lately it’s driving me insane so any support is very much appreciated.|

Hi globalethnographic.com administrator, Your posts are always well-supported by facts and figures.

Dear globalethnographic.com webmaster, Your posts are always well-referenced and credible.

Dear globalethnographic.com administrator, You always provide useful links and resources.

To the globalethnographic.com owner, Your posts are always informative and up-to-date.

To the globalethnographic.com administrator, Thanks for the well-structured and well-presented post!

To the globalethnographic.com administrator, Your posts are always well-supported and evidence-based.

Dear globalethnographic.com owner, Your posts are always informative.

To the globalethnographic.com webmaster, Your posts are always well-received by the community.

Dear globalethnographic.com admin, You always provide useful information.

Hello globalethnographic.com webmaster, You always provide practical solutions and recommendations.

Hello globalethnographic.com administrator, Your posts are always well-balanced and objective.

To the globalethnographic.com administrator, Your posts are always well-formatted and easy to read.

Hello globalethnographic.com webmaster, Thanks for the post!

To the globalethnographic.com administrator, Thanks for the well-structured and well-presented post!

Hi globalethnographic.com owner, Great job!

To the globalethnographic.com admin, You always provide useful information.

Hello globalethnographic.com owner, Great job!

affiliate marketing for ecommerce

PharmEmpire referral program

health product review sites

How to apply for a supplements affiliate program

hormone replacement therapy

hormone supplements for heart health and cholesterol

control

menopause relief online

low-cost hormone therapy for perimenopause

Hello globalethnographic.com owner, Thanks for the valuable information!

Hi globalethnographic.com admin, You always provide practical solutions and recommendations.

Hello globalethnographic.com owner, Great content!

Many thanks. Fantastic stuff.

Hello globalethnographic.com administrator, You always provide in-depth analysis and understanding.

Dear globalethnographic.com administrator, Thanks for the informative post!

To the globalethnographic.com webmaster, Your posts are always well thought out.

Dear globalethnographic.com admin, Your posts are always well-referenced and credible.

Hi globalethnographic.com admin, Thanks for the well written post!

It’s going to be finish of mine day, except before ending I

am reading this wonderful article to increase my knowledge.

To the globalethnographic.com administrator, Your posts are always on point.

Hi globalethnographic.com webmaster, Good to see your posts!

Hello globalethnographic.com webmaster, Your posts are always well-referenced and credible.

Hi globalethnographic.com webmaster, You always provide useful links and resources.

Dear globalethnographic.com owner, You always provide useful information.

Dear globalethnographic.com admin, Thanks for the well-structured and well-presented post!

Dear globalethnographic.com administrator, You always provide great examples and real-world applications.

To the globalethnographic.com admin, Great content!

Hello globalethnographic.com admin, Thanks for the well-written and informative post!

Hello globalethnographic.com webmaster, Your posts are always well-balanced and objective.

Hi globalethnographic.com owner, You always provide great examples and real-world applications.

Hello globalethnographic.com owner, Nice post!

Hello globalethnographic.com owner, Your posts are always a great read.

To the globalethnographic.com administrator, Thanks for the detailed post!

Helloo..

I highly recommend Mr Buckler,

Fix broken Relationship/Marriage..

Win back your Ex-Lover

Thank you so so much

????????????????????????????????????????????

Thanks million????????????

Reach.. R.buckler11 (((@gmail.com)))

To the globalethnographic.com admin, Your posts are always well-cited and reliable.

Dear globalethnographic.com owner, Your posts are always well written.

Hello globalethnographic.com webmaster, You always provide great examples and real-world applications.

Wow! This blog looks exactly like my old one! It’s on a entirely different topic but it has pretty much

the same page layout and design. Superb choice of colors!

Hello globalethnographic.com webmaster, You always provide great information and insights.

Hi to every body, it’s my first visit of this website; this webpage consists of awesome and in fact excellent material in support

of visitors.

It’s a pity you don’t have a donate button! I’d definitely donate to this

fantastic blog! I suppose for now i’ll settle for bookmarking and adding your

RSS feed to my Google account. I look forward to fresh updates and will talk about this blog with my Facebook group.

Chat soon!

I like what you guys are usually up too. This kind of clever work and reporting!

Keep up the good works guys I’ve incorporated you guys to blogroll.

Your style is so unique compared to other people I have read stuff

from. Many thanks for posting when you have the opportunity, Guess I’ll just bookmark this web site.

To the globalethnographic.com owner, Your posts are always on topic and relevant.

Hello globalethnographic.com admin, Thanks for the well-organized and comprehensive post!

I am sure this piece of writing has touched all the internet visitors, its really really good post on building up new web site.

I’m extremely impressed with your writing skills as well

as with the layout on your weblog. Is this a paid theme or did you modify it yourself?

Anyway keep up the excellent quality writing, it’s rare to see a nice blog like this one today.

Hello! I just wanted to ask if you ever have any issues with hackers?

My last blog (wordpress) was hacked and I ended up losing many months of hard work due to no back up.

Do you have any methods to prevent hackers?

An interesting discussion is worth comment. I believe that you should write more on this topic, it might not be a taboo matter but usually people don’t speak about such subjects.

To the next! Kind regards!!

Hello globalethnographic.com admin, You always provide clear explanations and step-by-step instructions.

To the globalethnographic.com webmaster, Good to see your posts!

Normally I do not read article on blogs, but I wish to say that this write-up very compelled me to

take a look at and do so! Your writing taste has been surprised me.

Thank you, very nice post.

To the globalethnographic.com administrator, Thanks for the well-organized post!

Dear globalethnographic.com owner, Your posts are always informative and well-explained.

Dear globalethnographic.com owner, You always provide clear explanations and step-by-step instructions.

mexico drug stores pharmacies: mexican online pharmacy – mexican rx online

canada rx pharmacy world: canada cloud pharmacy – online pharmacy canada

canadian pharmacy online reviews [url=https://canadapharmast.online/#]canadian king pharmacy[/url] best online canadian pharmacy

canadian pharmacy reviews: canadian drug pharmacy – canadian pharmacy antibiotics

http://indiapharmast.com/# best india pharmacy

reputable indian online pharmacy: cheapest online pharmacy india – reputable indian online pharmacy

world pharmacy india [url=https://indiapharmast.com/#]reputable indian online pharmacy[/url] reputable indian online pharmacy

india online pharmacy: online pharmacy india – Online medicine home delivery

canadian pharmacy ratings: canadian pharmacy store – canadian pharmacy price checker

http://canadapharmast.com/# trusted canadian pharmacy

mexican pharmacy: reputable mexican pharmacies online – buying from online mexican pharmacy

п»їbest mexican online pharmacies [url=http://foruspharma.com/#]mexico drug stores pharmacies[/url] best online pharmacies in mexico

cheapest online pharmacy india: india pharmacy – indian pharmacy paypal

online shopping pharmacy india: indianpharmacy com – india pharmacy

https://foruspharma.com/# reputable mexican pharmacies online

india pharmacy mail order: reputable indian pharmacies – top 10 online pharmacy in india

indianpharmacy com [url=https://indiapharmast.com/#]Online medicine order[/url] п»їlegitimate online pharmacies india

mexican drugstore online: mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs – purple pharmacy mexico price list

onlinepharmaciescanada com: safe canadian pharmacies – canadian pharmacy 24

purple pharmacy mexico price list: mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa – mexico drug stores pharmacies

https://doxycyclinedelivery.pro/# doxycycline 100mg cost in india

doxycycline 100mg cap tab: doxycycline 1mg – doxycycline price in india

https://amoxildelivery.pro/# amoxicillin without a prescription

can i buy cheap clomid without dr prescription [url=https://clomiddelivery.pro/#]can i order generic clomid without insurance[/url] get generic clomid no prescription

http://doxycyclinedelivery.pro/# doxycycline hyc

https://clomiddelivery.pro/# where to buy generic clomid without a prescription

http://amoxildelivery.pro/# amoxicillin pharmacy price

purchase cipro [url=https://ciprodelivery.pro/#]cipro online no prescription in the usa[/url] ciprofloxacin

http://amoxildelivery.pro/# amoxicillin 500mg pill

https://paxloviddelivery.pro/# paxlovid for sale

where to get clomid without dr prescription [url=http://clomiddelivery.pro/#]where buy clomid for sale[/url] cost clomid tablets

http://paxloviddelivery.pro/# Paxlovid over the counter

https://doxycyclinedelivery.pro/# can i buy 40mg doxycycline online

clomid otc [url=https://clomiddelivery.pro/#]where to get clomid price[/url] order clomid tablets

http://amoxildelivery.pro/# amoxicillin 500mg capsules antibiotic

http://paxloviddelivery.pro/# Paxlovid over the counter

doxycycline prescription australia [url=http://doxycyclinedelivery.pro/#]how to get doxycycline prescription[/url] buying doxycycline online

https://ciprodelivery.pro/# ciprofloxacin mail online

paxlovid price: paxlovid pill – Paxlovid over the counter

https://clomiddelivery.pro/# how to get generic clomid without dr prescription

https://clomiddelivery.pro/# can i get cheap clomid pills

buy cipro online without prescription [url=https://ciprodelivery.pro/#]ciprofloxacin[/url] cipro

http://paxloviddelivery.pro/# paxlovid price

http://paxloviddelivery.pro/# Paxlovid over the counter

doxycycline otc drug [url=https://doxycyclinedelivery.pro/#]doxycycline online uk[/url] average price of doxycycline

buy paxlovid online: paxlovid india – paxlovid buy